I am the master of my fate: I am the captain of my soul

– William Earnest Henley

That quote from the poem “Invictus” was the last statement of Tim McVeigh, another discontented citizen of the United States of America, otherwise known as “unitary bomber” (which Google seems to have a fucking big problem with) that led the biggest terrorist attack on the United States until Osama Bin Laden went one better. Well quite a bit better.

McVeigh was killed by lethal injection. Obama was machine gunned down whilst unarmed and his body discarded out the back of an American aircraft carrier [becoming yet another martyr].

Both men alleged that revenge motivated them….that was the spin put on it by the sepos.

At LF we call it as it was…at least to those responsible for the acts of terror/revenge – justice was the driver and they must feel that they succeeded as their respective acts are indelibly seared on the American psyche.

Both men were killed for their acts. One was an American citizen, and the other an Arab billionaire. Their intellectual and spiritual union? – evil can be invoiced – EOD explosion on delivery.

Osama Bin Laden & Timothy McViegh – Two men with the same objective – to control the excesses, criminality, and corruption of the United States Government

What made them act to murder Americans was to return “the flavour of the favour” – the delightful feeling of powerlessness mixed with the stench of decomposing human remains. Will someone invoice the New Zealand Government, and if so when, and why?

Brother in arms – scary resemblance indeed – Snowdon can’t be McVeigh? – but they had the same cause just different methodology. Both were hunted – till now Snowdon remains free thanks to the Russians, but he will face American justice as Osama did – shot dead in a country where the Americans did not have permission to enter.

New Zealand’s “so called” terrorist Tame Iti, according to the New Zealand Police, set up a terrorist training camp in Urewera – yeah right, but that was what the New Zealand Police wanted New Zealanders to believe because it suited the Governments purposes – suppression of the indigenous Maori seeking custody of sovereignty by highlighting their alleged propensity for violence.

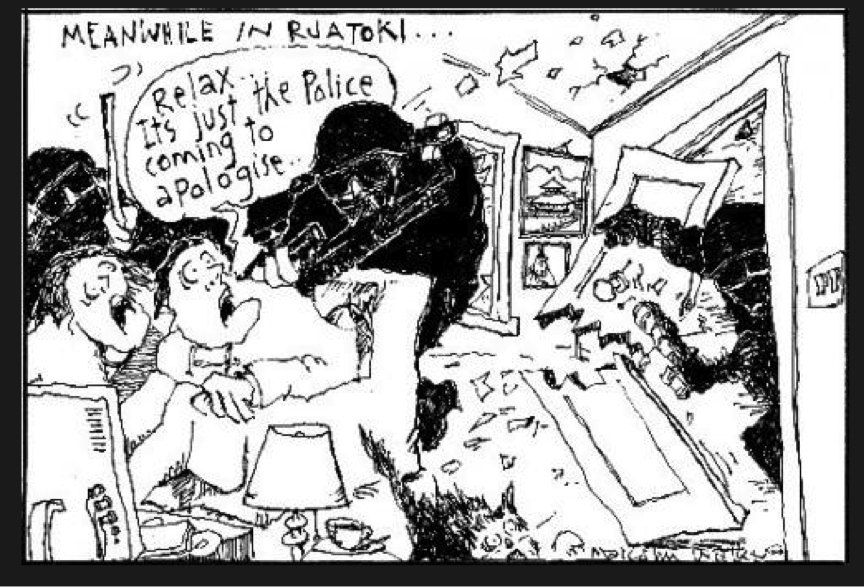

Images of terror – at the hands and guns of the New Zealand Police – look at the hidden face of the white supremacist that wants to remain secret as most cowards do – who needs the yanks when John Key makes George Bush look honest and capable. The handcuffed bloke in the “beanie” drove the school bus with 25 Maori kids on board. Egalitarian society – yeah right.

The following was a report from the Police cuddling New Zealand media;

Citing the Terrorism Suppression Act, police arrested 18 people in nationwide raids linked to alleged weapons-training camps near the eastern Bay of Plenty township of Rūātoki.

In addition to raids in Rūātoki and nearby Whakatāne, search warrants were also executed in Auckland, Wellington, Palmerston North and Hamilton. The raids followed 12 months of police surveillance of activist groups ranging from environmentalists to Māori separatists. Around 300 police, including members of the Armed Offenders and anti-terror squads, were involved in the raids. A small number of guns and 230 rounds of ammunition were seized.

Among those arrested was the veteran Tūhoe activist Tame Iti. Police claimed Iti was involved in running military-style training camps in the Urewera Ranges and was planning a guerrilla war to establish an independent state on traditional Tūhoe land. The Solicitor-General subsequently decided that there was insufficient evidence to lay charges under the Terrorism Suppression Act, which he said was ‘almost impossible to apply in a coherent manner’. However 16 people faced weapons charges.

Those arrested were released on bail within a month. After a lengthy legal process, charges against 11 of the 16 were dropped in September 2011; the Supreme Court ruled that the police had obtained evidence illegally. Another accused man had died in the meantime. Iti is one of four people who faced trial in the High Court in Auckland in February 2012 on charges of participating in a criminal group and possessing firearms. The jury was not able to agree on the former charge, but all four were found guilty of firearms offences. In May 2012 two received a sentence of nine months home detention and the other two – including Iti – were each sentenced to two-and-a-half years in prison.

The raids damaged the relationship between the police and Tūhoe. They were ordered by Police Commissioner Howard Broad, who on his retirement in 2010 promised to ‘stand and explain to Tuhoe what the police did’ – and if necessary apologise. The raids also complicated Tūhoe’s negotiations with the government over the iwi’s claims under the Treaty of Waitangi, though a full and final settlement was reached in September 2012.

The Ureweras had experienced similar police action before. In April 1916 a large force of heavily armed constables was sent to arrest the Tūhoe leader Rua Kēnana. Shooting broke out and two Māori, including Rua’s son, were killed. Rua’s trial in the Supreme Court was one of the longest in New Zealand’s legal history. He was found not guilty of sedition but guilty of resisting arrest and sentenced to one year’s hard labour, followed by 18 months’ imprisonment. The presiding officer, Judge Chapman, commented that Māori needed to learn that the law ‘reached every corner’ of the land. Eight members of the jury later spoke out against the harshness of this sentence.

Need we say more – fuck yeah. Out of control Police Officers – ask Kim Dotcom who had a visit from the same psychotic rapist brethren.

Fuck chopping down a flagpole, why not chop down a building “Osama style”? Tame Iti is the modern Hone Heke, and the similarities cannot be ignored.

Born at Pakaraka south of Kerikeri in the Bay of Islands, Heke was a highly influential chief of the Ngāpuhi tribe.

However, it was as a warrior and as a leader of Māori rebellion that Hone Heke is best known. He participated in Titore’s expedition to Tauranga, and fought with Titore against Pomare II in 1837.

The Treaty of Waitangi

Conflicting reports survive as to when Heke signed the Treaty of Waitangi. He may have signed with the other chiefs on 6 February 1840, but in any event, he soon found the agreement not to his liking.

Among other things, Heke objected to the relocation of the capital to Auckland; moreover the Governor-in-Council imposed a customs tariff on staple articles of trade that resulted in a dramatic fall in the number of whaling ships that visited Kororareka (over 20 whaling ships could anchor in the bay at any time. A reduction in the number of visiting ships caused a serious loss of revenue to Ngāpuhi.

Heke and his cousin Titore also collected and divided a levy of £5 on each ship entering the bay. Pomare felt aggrieved that he could no longer collect payment from American whaling and sealing ships that called at Otuihu across from Opua.

The British representative became concerned that Heke and the Ngāpuhi chief Pomare flew the American Ensign.

Heke and Pomare had listened to Captain William Mayhew, the Acting-Consul for the United States since 1840, and to other Americans talking about the successful revolt of the American colonies against England over the issue of taxation.

Heke obtained an American ensign from Henry Green Smith, a storekeeper at Wahapu who had succeeded Mayhew as Acting-Consul. After the flagstaff was cut down for a second time the Stars and Stripes flew from the carved sternpost of Heke’s war-canoe.

Letters from William Williams record talks he had with Heke, and refer to American traders attempting to undermine the British both before and especially after the signing of the treaty.

The first American Consul, William Mayhew, was probablypressured into leaving New Zealand, but was replaced by two unofficial Consuls, Green Smith and Waetford.

They continued in anti-British activities, selling muskets and powder to the disaffected Maori. Waetford was later convicted and imprisoned for gunrunning, but Green Smith successfully escaped New Zealand before the Crown could arrest him.

Bishop Pompallier, who led the Catholic missionaries, had advised several of the leading Catholic chiefs (such as Rewa and Te Kemara) to be very wary in signing the treaty, so it is not surprising that they had spoken out against the treaty.

William Colenso, the CMS missionary printer, in his record of the events of the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi commented that;

“after some little time Te Kemara came towards the table and affixed his sign to the parchment, stating that the Roman Catholic bishop (who had left the meeting before any of the chiefs had signed) had told him “not to write on the paper, for if he did he would be made a slave.“

The trial and execution of Wiremu Kingi Maketu in 1842 for murder was, in the opinion of Archdeacon Henry Williams, the beginning of Heke’s antagonism to the colonial administration, as Heke began gathering support among the Ngāpuhi for a rebellion against the colonial administration.

However it was not until 1844 that Heke sought the support of Te Ruki Kawiti and other leaders of the Ngāpuhi iwi by the conveying of ‘te ngākau’, the custom observed by those who sought help to settle a tribal grievance.

On 8 July 1844 the flagstaff on Maiki Hill at the north end of Kororareka was cut down for the first time by Heke’s ally Te Haratua, the chief of Pakaraka.

Heke himself had set out to cut down the flagstaff, but had been persuaded by Archdeacon William Williams not to do so.

As a signal of his unhappiness with the British, and encouraged by the American traders, in the space of six months Hone Heke returned to chop the flagpole down three times.

Heke had been strongly influenced by stories of the American War of Independence.

The uprising began when the flagpole was cut down for the fourth time at dawn on Tuesday 11 March 1845.

A force of about 600 Māori armed with muskets, double-barrelled guns and tomahawks attacked Kororareka.

Heke’s warriors attacked the guard post, killing all the defenders, and Heke cut down the flagstaff.

At the same time, possibly as a diversion, Te Ruki Kawiti and his men attacked the town of Kororareka.

The survivors from the 250 soldiers and settlers abandoned the town as HMS Hazard bombarded Hekes’ men with cannon.

Heke’s men then raided the town taking anything useful they could find. Heke’s order that the southern part of Korororeka remain untouched resulted in the Anglican and Catholic churches being undamaged.

Many Māori under the mana of the leading northern rangitira, Tāmati Wāka Nene, stayed loyal to the British government. They took an active part in the fight against Heke and tried to maintain a dialogue with the rebels in an effort to bring peace.

After the attack on Kororareka Heke and Kawiti, the warriors travelled inland to Lake Omapere, near to Kaikohe, some 20 miles (32 km), or two days travel, from the Bay of Islands. Nene built a pā close to Lake Omapere.

Heke’s pā named Puketutu, was 2 miles (3.2 km) away, while it is sometimes named as “Te Mawhe” however the hill of that name is some distance to the north-east.

In April 1845, during the time that the colonial forces were gathering in the Bay of Islands, the warriors of Heke and Nene fought many skirmishes on the small hill named Taumata-Karamu that was between the two pās, and on open country between Okaihau and Te Ahuahu.

Heke’s force numbered about three hundred men; Kawiti joined Heke towards the end of April with another hundred and fifty warriors.

Opposing Heke and Kawiti were about four hundred warriors that supported Tameti Waka Nene including the chiefs, Makoare Te Taonui and his son Aperahama Taonui, Mohi Tawhai, Arama Karaka Pi, Nopera and Pana-kareao.

Hone Heke built a pā at Puketutu on the shores of Lake Omapere (sometimes called Te Mawhe Pā). In May 1845 Heke’s Pā was attacked by troops from the 58th, 96th and 99th Regiments with marines and a Congreve rocket unit, under the command of Lt Col William Hulme.

The British troops had no heavy guns but they had brought with them a dozen Congreve rockets. The Māori had never seen rockets used and were anticipating a formidable display. Unfortunately the first two missed their target completely; the third hit the palisade, duly exploded and was seen to have done no damage. This display gave considerable encouragement to the Māori. Soon all the rockets had been expended leaving the palisade intact.

The tip of a Congreve rocket the same as used against Hone Hekes Pa – looks like a RPG of today. Could such weapons be used against the Governments “Pa’s”?

The storming parties began to advance, first crossing a narrow gulley between the lake and the pā.

Kawiti and his warriors arrived at the battle and engaged with the Colonial forces in the scrub and gullies around the pā. There followed a savage and confused battle.

Eventually the discipline and cohesiveness of the British troops began to prevail and the Māori were driven back inside the pā. But they were by no means beaten, far from it, as without artillery the British had no way to overcome the defences of the pā. Hulme decided to disengage and retreat back to the Bay of Islands.

In the Battle of Puketutu Pā, the British suffered 14 killed and 38 wounded. The Māori losses were 47 killed and about 80 wounded.

After the successful defence of Puketutu Pā on the shores of Lake Omapere, in accordance with Māori custom, the Puketutu Pā was abandoned as blood had been spilt there, so that the place became tapu.

Hone Heke returned to the pā he had built at Te Ahuahu. Tāmati Wāka Nene built a pā at Okaihau in the days that followed that battle at Puketutu Pā, the warriors of Heke Tāmati Wāka Nene fought several minor skirmishes with the warriors of Heke and Kawiti.

The hostilities disrupted the food production and in order to obtain provisions for his warriors, in early June 1845, Heke went to Kaikohe and on to Pakaraka to gather food supplies.

During his absence one of Tāmati Wāka Nene’s allies, the Hokianga chief, Makoare Te Taonui, attacked and captured Te Ahuahu. This was a tremendous blow to Heke’s mana or prestige, obviously it had to be recaptured as soon as possible.

Until the 1980s, histories of the Northern War tend to ignore the poorly documented Battle of Te Ahuahu, yet it was the most significant fight of the entire war as it is the only engagement that can be described as a clear victory – not for the British forces – but for Tāmati Wāka Nene and his warriors.

However, there are no detailed accounts of the action. It was fought entirely between the Māori warriors on 12 June 1845 near by Te Ahuahu at Pukenui – Hone Heke and his warriors against Tāmati Wāka Nene and his warriors.

As there was no official British involvement in the action there is little mention of the event in contemporary British accounts. Hugh Carleton (1874) mentions;

“Heke committed the error (against the advice of Pene Taui) of attacking Walker [Tāmati Wāka Nene], who had advanced to Pukenui. With four hundred men, he attacked about one hundred and fifty of Walker’s party, taking them also by surprise; but was beaten back with loss. Kahakaha was killed, Haratua was shot through the lungs”

The Rev. Richard Davis also recorded that;

“a sharp battle was fought on the 12th inst. between the loyal and disaffected natives. The disaffected, although consisting of 500 men, were kept at bay all day, and ultimately driven off the field by the loyalists, although their force did not exceed 100. Three of our people fell, two on the side of the disaffected, and one on the side of the loyalists. When the bodies were brought home, as one of them was a principal chief of great note and bravery, he was laid in state, about a hundred yards from our fence, before he was buried. The troops were in the Bay at the time, and were sent for by Walker, the conquering chief; but they were so tardy in their movements that they did not arrive at the seat of war to commence operations until the 24th inst.!”

At the Battle of Te Ahuahu on 12 June 1845 Nene’s warriors carried the day. Heke lost at least 30 warriors and was driven from Te Ahuahu leaving Tāmati Wāka Nene in control of Heke’s pā.

Haratua recovered from his wound. Heke was severely wounded and did not rejoin the conflict until some months later, at the closing phase of the Battle of Ruapekapeka.

After the battle of Te Ahuahu Heke went to Kaikohe to recover from his wounds. He was visited by Henry Williams and Robert Burrows, who hoped to persuade Heke to end the fighting.

The siege of Ruapekapeka began on 27 December 1845 and continued until 11 January 1846. This pā had been constructed by Te Ruki Kawiti to apply, and improve on, the defensive design used at Ohaeawai Pā; the external palisades at Ruapekapeka Pā provided a defence against cannon and musket fire and a barrier to attempted assaults on the pā.

Over two weeks, the British bombarded the pā with cannon fire until the external palisades were breached on 10 January 1846. On Sunday, 11 January Tāmati Wāka Nene‘s men discovered that the pā appeared to have been abandoned; although Te Ruki Kawiti and a few of his followers remained behind, and appeared to have been caught unaware by the British assault.

An assaulting force drove Kawiti and his warriors out of the pā. Fighting took place behind the pā and most casualties occurred in this phase of the battle.

It was later suggested that most of the Māori had been at church as many of them were devout Christians. Knowing that their enemy, the British, were also Christians they had not expected an attack on a Sunday.

The Rev. Richard Davis noted in his diary of 14 January 1846;

“Yesterday the news came that the Pa was taken on Sunday by the sailors, and that twelve Europeans were killed and thirty wounded. The native loss uncertain. It appears the natives did not expect fighting on the Sabbath, and were, the great part of them, out of the Pa, smoking and playing. It is also reported that the troops were assembling for service. The tars, having made a tolerable breach with their cannon on Saturday, took the opportunity of the careless position of the natives, and went into the Pa, but did not get possession without much hard fighting, hand to hand.”

However, later commentators cast doubt as to this explanation of the events of Sunday, 11 January as fighting continued on Sunday at the Battle of Ohaeawai.

Another explanation provided by later commentators is that Heke deliberately abandoned the pā to lay a trap in the surrounding bush as this would provide cover and give Heke a considerable advantage.

If this is the correct explanation, then the Heke’s ambush was only partially successful, as Kawiti’s men, fearing their chief had fallen, returned towards the pā and the British forces engaged in battle with the Māori rebels immediately behind the pā.

In any event after four hours of battle, the Māori rebels withdrew. The British forces, left in occupation of the pā, proclaimed a victory.

Shortly after Ruapekapeka, Heke and Kawiti met their principal Māori opponent, the loyalist chief, Tāmati Wāka Nene, and agreed upon peace.

Nene went to Auckland to tell the governor that peace had been won; with Nene insisting that the British accept the terms of Kawiti and Heke that they were to be unconditionally pardoned for their rebellion.

The governor, George Grey presented the end of the rebellion as a British victory. Grey had no respect for the political stance that Heke assumed and stated in John Key like arrogance;

“I cannot discover that the rebels have a single grievance to complain of which would in any degree extenuate their present conduct and. . . I believe that it arises from an irrational contempt of the powers of Great Britain”

Despite this, Heke and George Grey were reconciled at a meeting in 1848.

The ingenious design of the Ohaeawai Pā and the Ruapekapeka Pā became known to other Māori tribes.

These designs were the basis of what is now called the gunfighter pā that were built during the later New Zealand Wars.

The capture of Ruapekapeka Pā can be considered a British tactical victory, but it was purpose-built as a target for the British, and its loss was not damaging; Heke and Kawiti managed to escape with their forces intact.

It is clear that Kawiti and Heke made considerable gains from the war, despite the British victory at Ruapekapeka. After the war’s conclusion, Heke enjoyed a considerable surge in prestige and authority much like Tame Iti amongst modern day Maori.

The missionary Richard Davis, writing on the 28th August 1846, stated that Hone Heke had;

“amongst his countrymen, as a patriot, he has raised himself to the very pinnacle of honour, and is much respected wherever he goes”

Following the conflict Hone Heke retired to Kaikohe. There, two years later, he died of tuberculosis on 7 August 1850, a disease introduced by the British.

The Rev. Richard Davis performed a Christian ceremony and then one of his wives, Rongo and other followers, who had been his bodyguards for many years, took his body to a cave near Pakaraka, called Umakitera.

In April 2011 it was announced by David Rankin, of the Hone Heke Foundation, that the bones of Hone Heke would be moved and buried at a public cemetery, as the land near the cave was being developed, and in May 2011 he supervised the move; although some Ngāpuhi questioned his right to do so.

We can, here our loyal readership ask – what the fuck has Hone Heke, Timothy McVeigh and Osama Bin “fucking” Laden got to do with the Maori population of New Zealands prisons.

Quite simple really – it’s the breeding ground of violent revolution at great “personal” cost to those that ignore a reality. The New Zealand Government sent Tame Iti to prison on trumped up gun charges just like they did to Tuhoe’s previous leader Rua Kenana in 1916. But the difference now is that Iti could talk to a vast number of his race, whom some have spent most of their adult life in prison. History repeats, and we feel it necessary to repeat a media report about how history was repeated for the Tuhoe people:

The Ureweras had experienced similar police action before. In April 1916 a large force of heavily armed constables was sent to arrest the Tūhoe leader Rua Kēnana. Shooting broke out and two Māori, including Rua’s son, were killed. Rua’s trial in the Supreme Court was one of the longest in New Zealand’s legal history. He was found not guilty of sedition but guilty of resisting arrest and sentenced to one year’s hard labour, followed by 18 months’ imprisonment. The presiding officer, Judge Chapman, commented that Māori needed to learn that the law ‘reached every corner’ of the land. Eight members of the jury later spoke out against the harshness of this sentence.

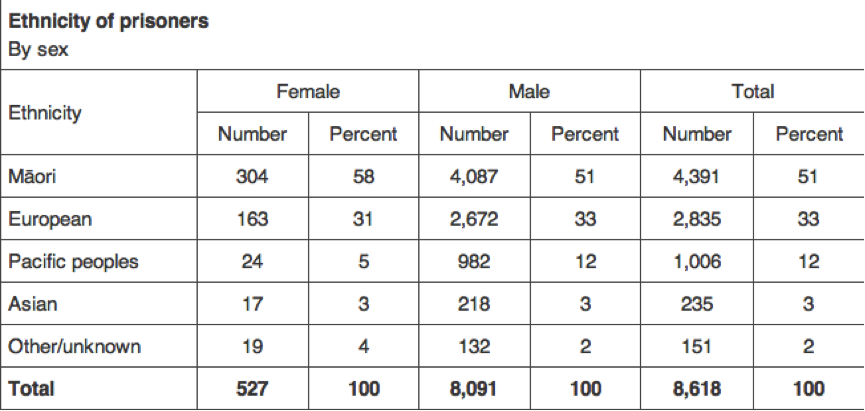

Those with some Maori blood make up 51% of the prison population, when the same racial group is only 15% of New Zealand population. The Courts call this “phenomenon” appalling, and in need of an answer in the long term.

District Court Judge Stephen O’Driscoll recently judicially noted that Maori offenders made up a disproportionately large element within the prison population.

O’Driscoll – A DCJ getting something accurate – yes it does happen. And he’s got a PHD in law – his thesis being miscarriages of justice caused by counsel behaviour

In the Global Peace Index New Zealand is ranked as one of the world’s most peaceful countries, having an internationally acclaimed reputation for social justice and equality.

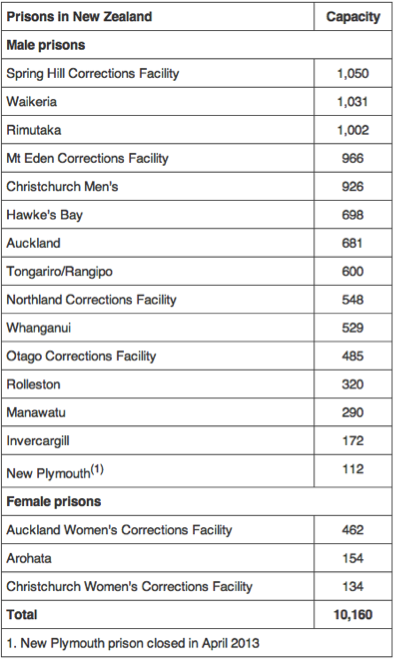

Contradicting this understanding internationally, New Zealand has the second highest rate of imprisonment in the western world. This is to say that of 10,160 current prisoners 5,182 prisoners are indigenous Maori, or of such descent.

If the stats are accurate;- of 4,433,000 citizens (est June 2012), Maori population is estimated at 664,954, [15%], and have 7.79% of their population behind bars. This relates to 7.79 per 100 Maori, or 77.9 per 1000. Now relate this to the following 2012 chart;

The prison population grew by over 1500 in a year, when diversion, and home detention is in significant play and where bail is at record numbers because of the lack of facilities. What is the real number of Maori in the “justice system”.

The prisoner increase in a year equates to a 17.9% rise, which would seem to disclose that New Zealand is a heap of trouble, when the crime rates have been falling for many years [according to police stats]. Of course Police information is notoriously dishonest and purposefully so.

If this trend continues it is possible that as many as 15,000 discontented Maori could be behind bars before 2020.

What would be enlightening is to have the numbers of Maori involved in that 17.9% increase. If the increase disclosed a far higher percentile than the average 51%, then that proves that the Maori race is on a hiding to nothing, and that the race will react to a charismatic leader coming up with a revolutionary solution.

The other stat that would be interesting is how the previous decades numbers relate to overall numbers of a race that has been in prison. It is said that every Maori knows a relative that has been inside. If this were true could this relate to 1 in 20 Maori have seen the inside of a cell.

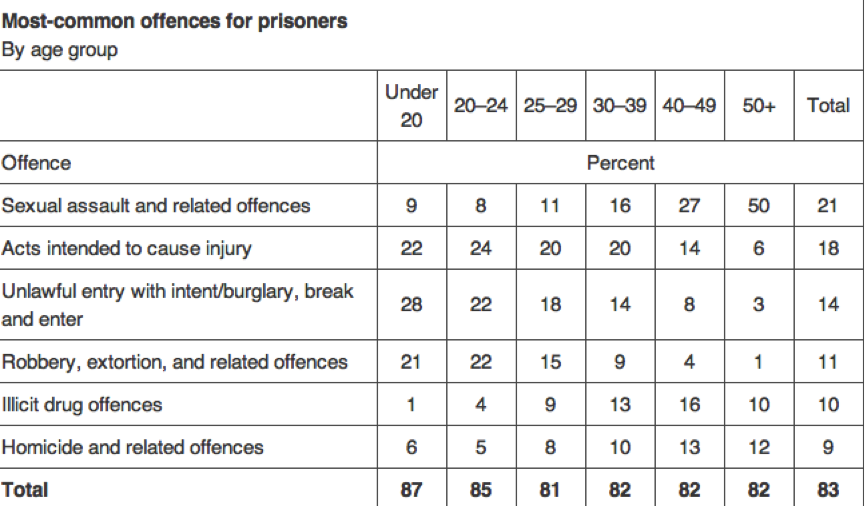

83% of prisoners have allegedly committed 6 types of crime.

Sexual assault and acts intended to injure come from the family unit and the immediate social circumstance during development. Is this where the failure is? And are Maori solely responsible for their predicament?

As for the New Zealand Police Services reasoning for rape, violence, and even murder, their problem is power. They can get away with it and do. Of course they are charging a few of the boys now and then just to keep the Politicians happy and to deceive New Zealanders as to the real situation. That being that there are likely more criminals, [as a percentile], in the New Zealand Police Force than there are in Maori. And their crimes are a lot more serious. Take a look at a message we received from a previous Police Officer Mike Chappell;

Mr Chappell – we would love to hear from you and get all the names and criminal or otherwise disingenuous actions of New Zealands largest criminal gang. You can email us direct, or we can in certain circumstances have an asset contact you.

What is most offensive about the Polices history of rape, violence, and general criminality is that they do not have the excuse that Maori do, yet they bag Maori – what is that about?

A “bad” upbringing is used frequently to explain the number of Maori that are in prison. But what is a bad upbringing? There are many success stories of young Maori who have come from a lower socio-economic background, but overall this is a tiny number, that would be best described as misleading as these persons have had opportunities most did not. The issue starts at the cot and ends at the coffin, and with an exponentially increasing number of the Maori, most of the “bit in the middle” is spent incarcerated.

Young Maori are exposed to violence not only at home but also at schools they attend, and certainly in the lower socio-economic neighborhoods they reside in. Kelston Boys High School is one such factory of thugs.

The Killing Fields of Kelston – a lower socio-economic area of West Auckland where young Maori men are taught the mantra that violence solves problems. Well maybe one day that will come back to haunt the “grasshoppers master”.

What would the prison population be without diversion and home detention, although it is suspected that Maori are significantly disadvantaged when it comes to applications for home detention given that you need to have a stable address and have the ability to be supported, or to support themself, and you cannot associate with persons that have served prison.

With most Maori families in certain districts, dad, mum, and granddad have likely done what is known colloquially as “boob” and all may live in the one house on social security benefits. Therefore, there is no way that home detention can be entertained.

In 1996/97 the average prison population was about 5000, and now some 16-17 years later it has doubled. This means that the number of Maori prisoners has doubled, and is set to double again.

John Key – the silent assassin of the Maori races aspirations to rule their own destiny – could this guy get his wish – be as famous as a Kennedy – it is 50 years since JFK had his head blown apart by a man acting alone?

One international study examining law and order across western nations attributes New Zealand’s failure to reduce the number of prisoners to its “tough on crime” approach by New Zealand’s political parties since the 1980’s, even though crime rates are low.

LF believes that given the Polices culture of raping, assaulting, and likely murdering [Dickie Maxwell] people they come into contact with, the position must worsen substantially where one calm sunny day the Police are going to make a very wrong move and all hell is going to break loose like it did in Waco Texas;

76 men women and children murdered by the US Government when it attempted to take guns off the Davidian section led by David Koresh. Could this be a New Zealand prison, or a police station? – where will the imbalance explode into action?

Today each prisoner costs on average $94,000 a year to lock up, and the current government has described New Zealand’s prison problem as a moral and fiscal failure.

Dr Pita Sharples came up with an alternative scheme for Maori imprisonment to try and keep recidivism as low as possible, but strangely the sheer cost of the current unsuccessful model meant that his less expensive model went nowhere. How does that work?

An intelligent pacifist leader of Maori whose ideas to solve recidivism are not controversial, just unaffordable because the current model is so expensive that no money is around. But why is the Government hell bent on building a stock of prisons?

LF thinks no matter the “good words” of the politicians and judiciary – they just don’t give a fuck – that is until they are looking down a political reality that builds political prisoners, and not criminals.

The British built the “MAZE” to hold hundreds of Irish Political Prisoners who were released at the end of hostilities. The prison solved nothing. It was a breeding ground.

Related articles

- Mana ‘trampled’ by Te Urewera raids, says HRC report (radionz.co.nz)

- Urewera raids traumatised people (stuff.co.nz)

- Police commissioner wants to visit Ruatoki before April (radionz.co.nz)

- Project under way to cut Te Urewera pests (radionz.co.nz)

- NZ Politics Daily: 21 March 2012 (liberation.typepad.com)

- New Zealand Exemplars of Anti-Racism Best Practice (treatypeople.wordpress.com)

- Why New Zealand needs a written constitution (thekiwisonfire.wordpress.com)

- Bid to get more children into historic grounds (nzherald.co.nz)

- Operation 8 answers sought (stuff.co.nz)

- Showing the power of protest (stuff.co.nz)

No Comments

Who does your research they should be given recognition. Amazing piece of research mixed with what looks like a not so distant reality. It makes you realise how Maori were robbed under threat of death by the british, and that in the modern world, surely, they deserve more recognition than a couple of billion dollars.